Why it Could be Time to 'Go Private'

By Gavin Slader, Co-Head of Investment Banking and Head of Mergers & Acquisitions, JMP Securities, A Citizens Company

Key takeaways

- Go-privates involving private equity funds have been on the rise for the last five years and could be poised for even more activity in 2022.

- Amid headwinds in the equity markets, private equity funds and other investors may see attractive valuations as an opportunity to acquire select public companies and take them private.

- With public and private capital both plentiful, despite a tightening debt market, it could become more commonplace for companies to cycle between public and private ownership to capture the relative benefits of each.

If 2021 was the year of the IPO, 2022 could well be the year of the “go-private.” IPOs are plentiful in booming markets but dip in down markets as private owners face lower valuations and muted investor demand for new equity issuances. In contrast, go-privates could follow the opposite trend – privatization could be an especially appealing option for buyers in markets, when valuations are low.

“Go-privates” or “take privates” are transactions where a public company becomes privately held again through a private equity transaction, management buyout or purchase by another private buyer.

With market headwinds ongoing, middle-market companies could see a wave of go-privates among peers and competitors – and may want to consider the costs and benefits themselves. Here, we consider the backdrop for go-privates and some of the reasons why companies go that route.

Public/Private Capital Cycles in the Modern Market

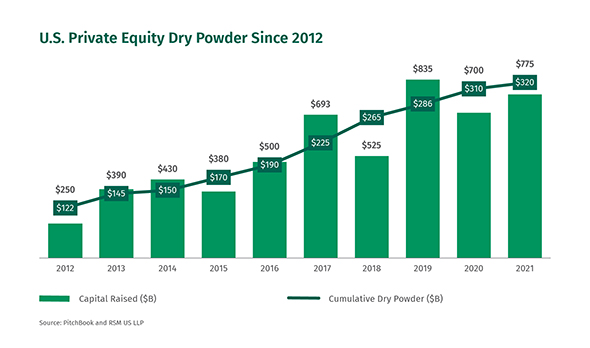

Go-privates involving private equity have been on an upward trend since 2017, according to data from S&P Global. The growing balance of capital in private equity funds is a key factor, as more funds compete for opportunities to put dry powder to work within their committed-capital deadlines. As of year-end 2021, the market capitalization for U.S. public equities was about $53.37 trillion, according to Siblis Research, a global data provider. Meanwhile, as of July 2021, U.S. PE funds were holding about $9.8 trillion in equity investments, according to McKinsey, a consulting firm. By the end of 2021, dry powder set another record at $3.4 trillion, according to Bain & Company, a consulting firm. PE capital is now present in most sectors and across market-cap sizes.

When public and private capital are both plentiful and accessible, markets could see more companies strategically cycling between the two forms. Quite a few companies have made that move historically, including Hilton Hotels, Dell Computers, Burger King, and Kinder Morgan, among others.

Both forms of ownership offer advantages and costs. Going public is a popular exit strategy to monetize equity positions for private investors, including founders, venture capital or private equity owners. Companies often turn to public markets to raise money for capital expenditures or to create public shares that are flexible currency for acquisitions. However, public ownership imposes high compliance costs on companies. It also creates a structure that emphasizes shorter-term results, with a hyperfocus on meeting publicly stated revenue and earnings targets.

Five Reasons Why Public Companies Go Private Again

We see a few common themes across companies that go from public to private:

- For a pure-play investment opportunity.

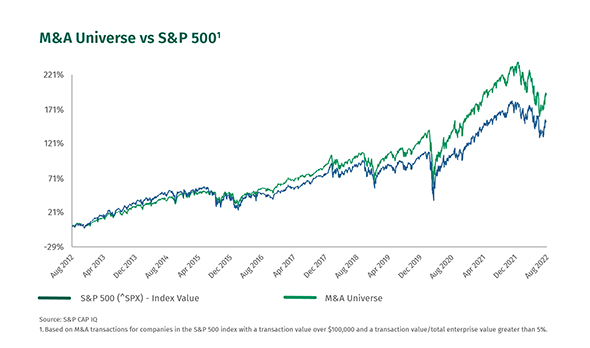

Perhaps the most common reason for go-privates is a valuation opportunity. Just as private equity and other private owners aim to sell assets at high valuations, they are always looking to buy low. In an environment like the first half of 2022, where public stocks and valuations are down, the window of opportunity to put dry powder to work is especially appealing to private buyers. Indeed, this strategic timing could contribute to the higher median returns of private equity versus public equity over a long time period.

- To make investments or strategic decisions that public markets may punish.

Public markets are notorious for putting pressure on management teams to meet or exceed short-term targets. This is unfortunately a counterproductive phenomenon; short-term performance often comes at the expense of long-term investments.

According to research from the CFA (Chartered Financial Analyst) Institute, short-termism can actually punish long-term profit trends for companies. In a 2020 study titled Short-Termism Revisited, researchers found that firms that focus on beating prior quarters’ earnings spend less on capital expenditures and have lower future earnings, compared to peers. By going private, companies could potentially escape these trends and align resources to longer-term goals.

In practice, this could mean doing a brand refresh or making other costly capital outlays. For instance, in the restaurant world, national brands need periodic renovations. Think of deteriorating competitive positioning at a fast-food franchise, which must undergo substantial updates to storefronts and menus to refresh their appeal to customers.

Acquisitions can also fall under this category. Public markets are known for punishing the stock prices of acquirers. Companies that aim to make multiple acquisitions could find that private ownership offers a more forgiving structure for conducting transactions, even if the acquirer loses the possibility of using public shares to make acquisitions. Indeed, recent research on this long-studied topic suggests that cash acquisitions often drive better returns than stock acquisitions, which may be conducted precisely because a company’s stock is “overvalued.”

Difficult restructuring choices can also be publicly unpopular. Layoffs, divestments and other corporate “housecleaning” actions could receive public backlash and punitive reactions in the company’s stock price, even if the steps would ultimately leave the company in a better long-term position. Restructuring can be poorly received by employees especially, though it can be a critical step for companies amid changing industry dynamics. Public ownership might discourage management from making such moves under the hyper-watchful audience of public shareholders.

- To capture the control premium for strategic reasons or governance changes.

The control premium is another well-studied phenomenon, where owners will pay a premium to hold majority control over a company, giving them the power to make major decisions. Control premiums can allow owners to enact changes that may drive an advantage strategically – or they may allow owners to implement valuable governance changes.

This was a key ingredient in one of the major go-private transactions of the modern era, when founder Michael Dell partnered with PE firm Silver Lake Partners and other private investors in 2013 to take the computing company private again and reestablish its strategic course.

- To deal with special circumstances, like bankruptcy or spinoffs.

Some go-private deals are related to more narrow circumstances, like transitioning assets out of a distressed or bankrupt company. In these circumstances, management teams can partner with private equity or other funding sources to conduct a management buyout or carve-out sale for a business or division.

- To capture the ‘financial engineering’ alpha.

The leveraged buyout or LBO was a key driver of the private equity industry in the early days and it continues to be a motivating factor for taking public companies private. If an unleveraged company is earning a 10% return on equity (ROE), a 50% leveraged company will earn twice as much in ROE.

The market conditions factor heavily into the appeal of an LBO. When the debt markets are tight and interest rates are high, leverage is a much higher risk – but when capital is flowing and interest rates are low, more buyers will be willing to take on leverage.

The 4% Bonus for Going Private

Public companies incur significant expenses related to compliance and reporting. A 2021 academic study titled Regulatory Costs of Being Public: Evidence from Bunching Estimation, estimated that the cost of public ownership was around 4% of market cap, per year, for U.S. firms. In practice, the costs are staffing hours – for accountants, compliance and investor relations staff. Cost savings alone are rarely the top driver of a privatization, but they are definitely a bonus for companies that go private for other reasons.

The Basics of Going Private

For public companies considering going private, there are a few key milestones to address. First, there’s the profile of buyers and/or financing arrangements. Many go-private transactions are conducted by external buyers, like private equity funds, using cash and loan financing. If the buyers are internal, such as a management-led buyout or founder-led buyout, the financing arrangements can involve a consortium of funds or loans along with cash. Second, public shareholders must approve the transaction. To entice their approval, acquisitions are usually done at a takeout premium (a premium to the prevailing public share price). Last, a go-private deal must include a long-term strategy, such as the possibility of re-listing shares publicly after some time, selling to a different private buyer in the future, or remaining privately held indefinitely.

Assessing the Road Ahead for Go-Privates

IPOs are already down in 2022, compared to the prior year, while public markets face continued headwinds. In light of the valuation advantages to taking public companies private, these conditions could prove favorable for privatizations. Public companies have an opportunity to assess the benefits that come along with the strategic capital decisions to go private. Companies that are not assessing the opportunity may find that peers and competitors are taking advantage of the environment to go private, driving competitive advantages in their spending or restructuring decisions in the years ahead.

Three considerations for managers and shareholders of publicly traded middle-market companies:

- Assess medium-term goals. Company stakeholders can conduct a full review of medium- or long-horizon goals, which could be well-served by private ownerships. Housekeeping opportunities like restructuring or large capital expenditures may be more successful and encounter fewer barriers with private ownership than with public capital, ultimately positioning a company for better future earnings.

- Watch competitors and peers. Keep an eye on the competitor set for the industry. In an environment that favors privatization, the competitive landscape may change significantly if peers move to private capital for strategic advantages.

- Weigh the benefits and costs of public ownership. Public ownership does offer substantial benefits, including liquidity for owners and stock as a valuable currency for management compensation and for acquisitions. However, it comes with substantial costs, like the annual expenses of complying with regulations and the pressure to deliver quarterly results. It can be a valuable process to review the company’s specific costs and benefits as it relates to public ownership.

Gavin Slader is a Managing Director and is co-head of investment banking at JMP Securities. He also serves as head of mergers and acquisitions. Gavin is a member of the firm’s executive committee.

Related Reading

M&A Deal Making Dynamics

Learn how private equity firms are playing a bigger role in the M&A deal making process. Deals involving PE firms have almost tripled in a decade.

4 Surprising 2022 M&A Trends

Following near record level valuations in 2021, find out what PE and corporate executives are expecting for their performance in the year ahead and what factors are presenting the biggest challenges.

The public to private equity pivot continues

As the private capital ecosystem has expanded over the last 25 years, the private equity-backed company count has climbed, while the number of public companies has fallen sharply. Explore what these trends mean for midsized companies.

Ready to take the next step? Get in touch with our team.

All fields are required unless marked as "Optional".

© Citizens Financial Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Citizens Bank, N.A. Member FDIC

“Citizens” is the marketing name for the business of Citizens Financial Group, Inc. (“CFG”) and its subsidiaries. “Citizens Capital Markets & Advisory” is the marketing name for the investment banking, research, sales, and trading activities of our institutional broker-dealer, Citizens JMP Securities, LLC (“CJMPS”), Member FINRA and SIPC (See FINRA BrokerCheck and SIPC.org). Securities products and services are offered to institutional clients through CJMPS. (CJMPS disclosures and CJMP Form CRS). Banking products and services are offered through Citizens Bank, N.A., Member FDIC. Citizens Valuation Services is a business division of Willamette Management Associates, Inc. (a wholly owned subsidiary of CFG).

Securities and investment products are subject to risk, including principal amount invested and are: NOT FDIC INSURED · NOT BANK GUARANTEED · MAY LOSE VALUE