Decreasing Business Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Why it matters

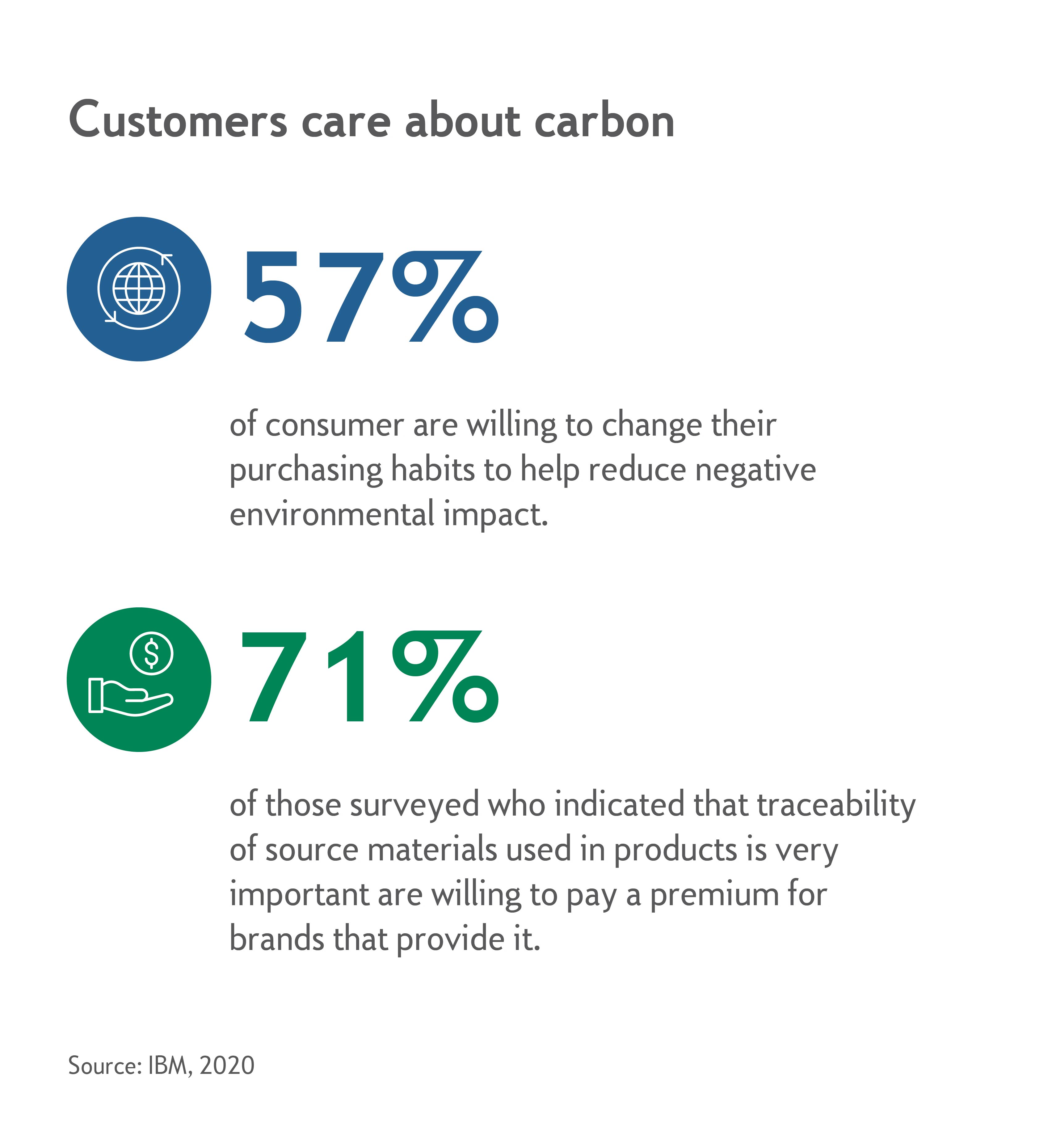

- Businesses are facing real consequences for their stance and actions on climate change, not just from regulators, but from customers and employees.

- Climate action plans (CAPs) are increasingly common and offer a framework for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions created by businesses.

- Because GHG and carbon accounting can be complex, many companies start with the GHG emissions from their own operations, and address peripheral and indirect GHG sources over time.

- Most strategies to reduce GHGs generate a positive return on investment (ROI) as energy-efficiency upgrades lead to lower operating costs, and help protect against the reputational risk of inaction.

Climate change has become a mainstream topic and middle-market companies are starting to face real consequences for their action or inaction. Taking steps to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the primary cause of climate change, is not only the ethical choice. Increasingly, it is a regulatory requirement, and a policy that many customers and employees are demanding from companies. GHG reduction can also be a profitable undertaking for many businesses.

For companies starting to consider their GHG impact and what steps to take, it helps to create a policy that aligns industry trends and emerging best practices. A climate action plan (CAP) is a popular framework that can help businesses establish a policy. However, it can be intimidating to get started. Fortunately, all action is good action—companies can see both environmental and reputational benefits just for getting started. For each company, the CAP process is a journey.

Understanding climate action plans

A CAP refers to an organization’s policy on GHGs, its stated goals for reducing them, milestone dates, and an analysis of financial barriers and opportunities, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, a research arm of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Some produce a CAP as a standalone document, while others include it as part of a broader sustainability plan that can include policies on other environmental, social, or economic issues. Many companies make their CAPs publicly available, but it mainly functions as an internal guide for those who aren’t yet ready to present a formal plan to the public.

A typical climate action plan

Most CAPs include:

- The company policy on greenhouse gas emissions

- Stated targets for emissions

- Milestone dates

- An analysis of financial barriers and opportunities

CAPs can be powerful tools for aligning intentions with actions and reaping the rewards. But there is another benefit to the CAP-creation process. Doing so helps organizations establish a level of climate literacy. GHG emissions and other environmental issues are an evolving subject area. The conversation is just beginning to coalesce around best practices and standards. The CAP process requires research and substantial discussion among a core group of policy setters in an organization. By the end of the process, companies will have created a shared climate literacy and ideally, buy-in from stakeholders across the business.

Step 1: Measure your carbon footprint

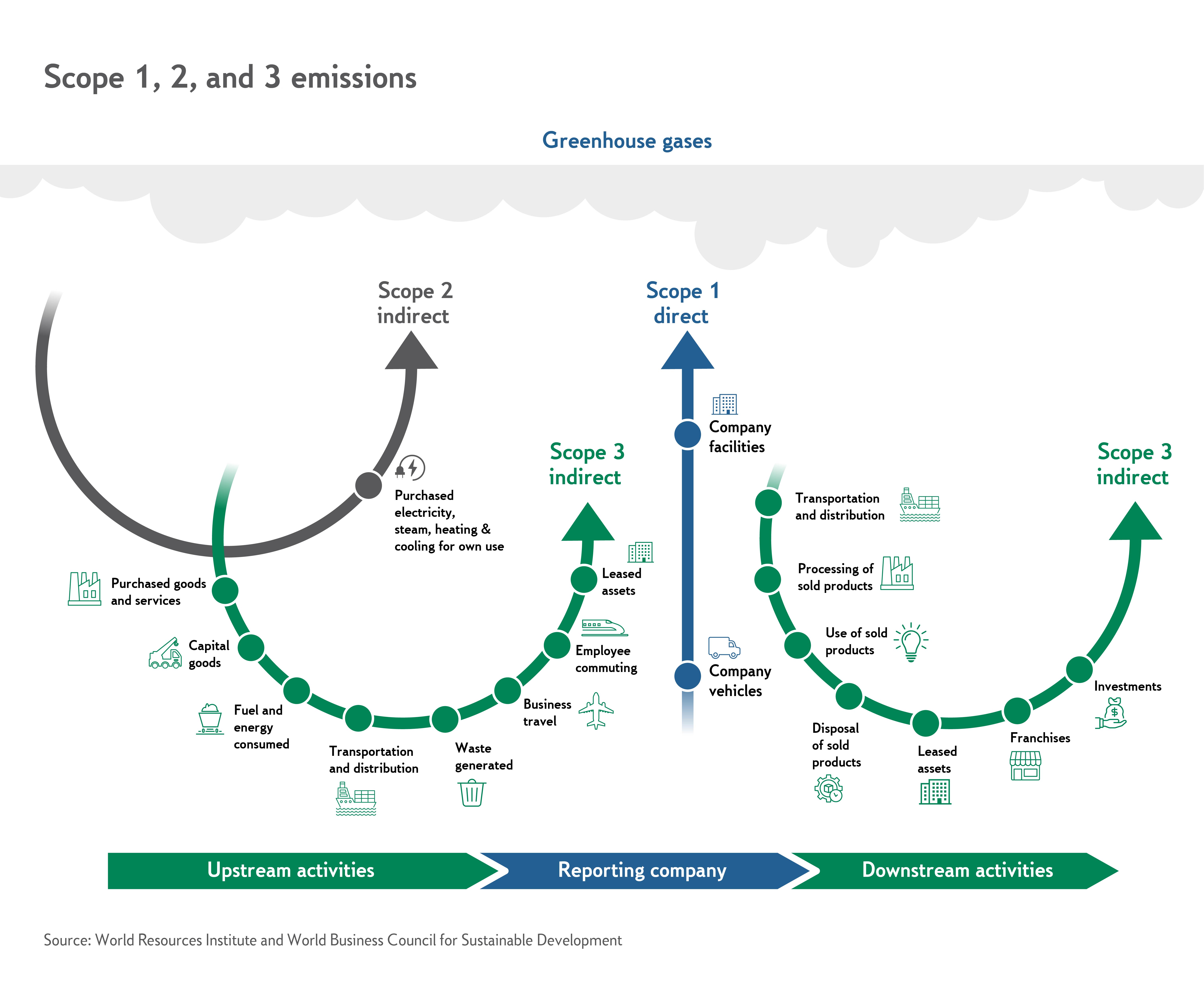

The first step in preparing a CAP is to measure the current carbon footprint of a business. There are three zones to inventory during this process, known as Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions.

Scope 1 or direct emissions include GHGs explicitly created by the business. This covers both “stationary combustion” of fossil fuels for company-owned boilers, turbines, or process heat, and “mobile combustion,” of GHGs produced by company vehicles.

Scopes 2 emissions, known as indirect emissions, include the GHGs generated by the production of electricity, steam, heating, or cooling that the company purchases for its use.

Scope 3 emissions cover every other indirect source of GHG production throughout the supply chain and lifecycle of a product or service. These emissions are created by suppliers, the transport of products or supplies, business travel and employee commuting, the operations of leased assets, and even the operations of any investments held by a company.

Emissions in Scope 3 may be so broad they are not yet measurable by a business. This will surely improve over time, as carbon accounting and CAPs become more mainstream and potentially even required by regulators. For organizations just beginning the “emissions policy” journey, Scopes 1 and 2 are a powerful starting point. In fact, it is common practice today for companies to publish a CAP that only has explicit goals for Scopes 1 and 2.

While it may seem daunting at first to conduct an inventory of emissions, the list of items for calculating Scope 1 and 2 is quite short. For Scope 1, companies need to know their fuel consumption. This can be measured through gallons of gas and other fuels purchased annually or approximated by using miles traveled by vehicle fleets and their average mileage standards. For Scope 2, utility bills for company properties have all the information a company needs on kilowatt hours (kWh) consumed annually. These companies will also need information about the energy sources used by the utilities to calculate Scope 1. There are many GHG emissions calculators available online to help companies translate their raw consumption data into emission estimates.

Once a company has totaled its annual emissions, it can produce more informative metrics. For example, the GHGs produced per hour, day, or year. Some use GHG per dollar of revenue, per employee, per square foot of operating space, or per product, to calculate emissions. These types of metrics can be more suited toward goal setting, rather than the absolute total of GHG emissions.

Step 2: Setting the right goal for your company

Once a company knows the current measure of its GHG emissions, it can consider targets and timelines.

The gold standard in GHG target setting is known as a “science-based target.” A true science-based target is one that was reviewed, approved, and monitored by the Science Based Targets Initiative, or SBTi, a non-governmental organization. The SBTi represents a partnership between the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), a non-profit that runs the global environmental disclosure system for companies, the United Nations Global Compact, the World Resources Institute, and the World Wide Fund for Nature. SBTi sets GHG-reduction “pathways” – meaning reduction targets for each year – that scientifically align with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting climate change to two degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels.

How many S&P 500 companies have a climate action plan

33% have set ambitious targets

24% have set weak targets

43% have not set a target

Source: Institutional Shareholder Services, 2021

Adhering to the science-based target is admirable, but it may be too complex or costly for companies just beginning the CAP process. Plus, as mentioned, it is not yet feasible to inventory Scope 3 emissions in many industries.

Instead, many companies start with a “science-aligned target,” which is a way of saying they are attempting to align with the SBTi standards but are unable to obtain full certification. SBTi publicly provides target GHG-reduction pathways by sector, some of which are finalized, and some of which are still in development.

For companies that aren’t prepared even for the science-aligned target, there is always the option of starting with a simpler target representing a percentage reduction and a timeline – not letting the perfect stand in the way of the good. As a reference point, SBTi recently announced that 338 early SBTi target-setters reduced GHG emissions by 25% in the first five years after the Paris Agreement, although global emissions from energy and industrial processes rose 3.4% over the same period, according to SBTi.

Step 3: Make changes

The final step in the CAP process is to assess the options for reducing GHG emissions. This part of the process enables companies to understand the impact of each potential change alongside the required investment and payback periods.

In terms of energy consumption, many companies benefit by updating facility lighting, an easy and relatively low-investment change. Upgrading heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning units in buildings to energy-efficient models added insulation and more efficient appliances can also drive substantial energy savings. Meanwhile, many regions now have access to renewable energy sources through their utility companies. An initiative called RE100, led by the CDP, publicizes the commitments of global corporations that use 100% renewable energy.

In terms of combustible fuel consumption, updating a fleet to electric or hybrid vehicles can be a high upfront cost depending on the business type. However, it’s the only substantial option for reducing direct emissions from automotive miles traveled--aside from finding a way to cut annual mileage. In terms of indirect travel emissions, reducing business travel and commuting are impactful changes, as are policies that encourage employee use of public transit or carpooling.

The payback period for greening

The payback period for GHG-reducing initiatives often takes time, but investments in greening pay off eventually as they lower operating costs.

Less than 2 years The typical payback period for solar hot water heating

2 to 4 years The payback for replacing older lighting with the newest versions of high efficiency lighting

7 to 20 years The payback for investing in a green building

5 to 6 years The payback for switching to electric vehicles

Source: EHS Today and McKinsey

Most GHG-reduction efforts will require some investment, but nearly all will pay off, since they’ll reduce future operating costs. Companies should conduct a simple payback period analysis to aid their decision-making. While green investments may not match or exceed the returns of your next new profitable business opportunities, they may generate a positive ROI and enhance your reputation.

"Sustainable" or "green" financing can potentially help companies meet their ESG goals. The terms sustainable financing or green financing can be used for an assortment of investments, but they all share one characteristic: they are connected to initiatives that improve the environment. "Green bonds" are fixed income securities issued by corporations or government entities earmarked to raise money for climate and environmental projects, such as those that improve energy efficiency, prevent pollution, clean transportation, and more. These bonds sometimes carry tax advantages akin to municipal bonds, depending on the issuer. "Sustainable deposits" are another example of environmental financing, in which retail or commercial banks earmark customer deposits for funding environmental projects.

Advanced strategies: Upstream and downstream

After a company masters the basics of creating and acting on a CAP, it will be ready for the more advanced strategies that require carbon accounting—upstream and downstream. Upstream refers to the supply chain and the production process—including GHGs produced by suppliers and outsourced operations, as well as employee activities like business travel and commuting. Downstream activities include everything that happens after the sale: further processing of a product, transport and distribution, the use of sold products, and the GHGs produced by any investments held by the company.

Right now, carbon accounting can be far more complex for upstream and downstream activities, and impossible for some industries. However, companies can begin the monitoring and data-gathering process. In the same way that many are beginning to monitor diversity and equality metrics across their suppliers and vendors, these companies can also begin to monitor GHG emissions throughout the value chain.

Bringing in help may be a good option

For most middle-market companies, the CAP process starts with facilities and operations teams, or through a company committee that includes these groups as well as accounting, finance and management. The right mix of skills and inputs will depend on the specific activities and structure of each company. It’s up to company executives and leadership to think through the team and the process that would suit their business.

There are also many consultants in the field. As the global thinking about climate change advances, the array of service providers has expanded to include sustainability consultants, carbon accountants, and climate strategists.

These specialists can be a valuable resource as companies embark on their CAP journey. However, it’s important to note that, in an evolving discipline, the type and quality of services provided through such consultants can vary widely. Companies that are considering an investment in a climate-change expert, for example, need to identify beforehand what type of assistance is needed from an outside expert, and look for a team or person with specific experience in the field. An experienced expert can help companies navigate the process, but not all providers live up to their marketing.

Any action beats inaction

Climate action plans can represent a simple starting effort or a complex undertaking. For middle-market leaders at the beginning of the journey, it’s important to note that any progress is good progress. Companies are starting to face penalties in the marketplace for inaction, whether that’s from unhappy customers or unsatisfied employees. On the other hand, all efforts and successes, even those that fall short of goals, are a marker of good intentions. No businesses are being penalized for struggling as they strive to do better—it is the progress that counts.

Climate action plans: Takeaways

- The jargon and science of climate change initiatives can be intimidating, but the process of establishing a CAP is doable for middle-market companies using information they already have on hand.

- Taking action on the basic GHG emission sources is quite effective, whereas inaction is increasingly a liability, not just for regulatory requirements, but for keeping customers and employees happy.

- Though the ROI is usually lower than competing business projects, most investments to reduce GHGs are profitable because they lower operating costs over time.

- Outside consultants can be a useful resource, but it’s important to first establish exactly what you need and find experts who have such experience in a still-evolving field.

Related Reading

Payables and Receivables Innovation

Find out why speed, accuracy and connectivity will define the future for treasury management.

What Treasurers Need to Know about Cyber Risk

As businesses achieve greater digitization in areas like payables, there may be more access points for cyber criminals to exploit.

Financing with Asset-Based Lending

How asset-based lending can help you manage the ups and downs of the economic cycle.

Ready to take the next step? Get in touch with our team.

All fields are required unless marked as "Optional".

© Citizens Financial Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Citizens Bank, N.A. Member FDIC

“Citizens” is the marketing name for the business of Citizens Financial Group, Inc. (“CFG”) and its subsidiaries. “Citizens Capital Markets & Advisory” is the marketing name for the investment banking, research, sales, and trading activities of our institutional broker-dealer, Citizens JMP Securities, LLC (“CJMPS”), Member FINRA and SIPC (See FINRA BrokerCheck and SIPC.org). Securities products and services are offered to institutional clients through CJMPS. (CJMPS disclosures and CJMP Form CRS). Banking products and services are offered through Citizens Bank, N.A., Member FDIC. Citizens Valuation Services is a business division of Willamette Management Associates, Inc. (a wholly owned subsidiary of CFG).

Securities and investment products are subject to risk, including principal amount invested and are: NOT FDIC INSURED · NOT BANK GUARANTEED · MAY LOSE VALUE